The Program was so much better than Priya had expected.

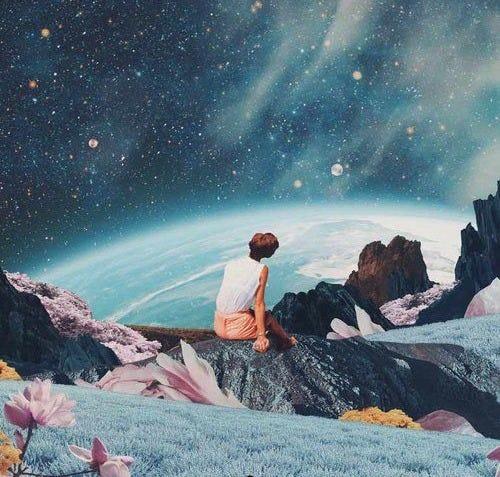

The sky had a dreamlike quality, hyperrealistic, each swelling cloud in sharp and sparkling relief. It was tinted a delicate blue that she couldn’t quite put a name to. A certain flower had once graced her grandmother’s china tea set: Myosotis sylvatica. Forget-me-not.

She wore a yellow dress with airy bell sleeves. It wasn’t something she would have necessarily picked out for herself, but she felt that the privilege of being in the garden warranted some grace given to what was clearly the Program’s optimized clothing option for her parameters. The flowy fabric was much more comfortable than her colony uniform.

She inhaled. The air was kinder here, gentle in her throat the way it never was in the colonies. It was sweet with the scent of tender green stems and the sun-warmed soil. Still rooted in the same spot, she reached down and caressed a flower with petals so velvety-fine that even the finely woven fabric of her dress was burlap in comparison.

The Council, allegedly, had made every attempt to ensure civilian satisfaction with the latest round of standard-issue colony uniforms, but they continued to feel suspiciously rough to the touch even after many washes.

Priya reached downward, groping for her cane, only to find empty space. In fact, even the persistent ache in her left hip had vanished. She remembered the Program briefings, remembered learning that the neural link did not transmit one’s preexisting physical pain into the simulation, as it was designed to allow the elderly a reprieve from their aging and pain-riddled bodies.

She felt young again, whole again. She wanted to kneel in the dirt and muddy the spotless buttercup dress; to shout for joy and scamper around the field like a puppy; to taste the sharpness of a freshly plucked wild dandelion. How beautiful it was, this Earth.

She let herself stand there for a moment, taking it all in.

It would be wrong, she knew, to say that she was alone. The longer she stood still, the more she became breathlessly aware of the immeasurable magnitude of life—for in the waving grass there were hundreds of bees, each with a mission to accomplish. She knew that thousands of earthworms had churned dead soil into the rich loam beneath her feet; that water coursed through the millions of delicate green stalks that surrounded her. A cacophony of birdsong exploded in the gnarled, budding trunks, weaving a fabric of harmonies unintelligible to the human ear. Where had they sourced the audio files? She assumed that the birdsong, at least, had been patched together from the defunct Internet, which was now only used by Council workers as a source of historical data.

But where they had discovered that low bee-frequency, she didn’t know.

It was one of those things that she assumed had been lost in the post-Takeover years; one of those Earthbound phenomena that she really hadn’t thought about in a long time. She didn’t recall missing it, or even noticing its absence. It had been so long since she had spent any significant time on Earth that some of its most fundamental elements had ceased to take up brainspace.

Here, however, the constant thrum of the bees awakened a yearning she had forgotten she could possess. She stood in the sun, steeping like one of her grandmother’s bergamot tea bags, pricklingly aware of everything around her. The infinite kaleidoscopic patterns of shade-dapple. The distant clamor of a rain-swollen creek. The itch of the wild grasses against her bare ankles, tempered by the tiny kisses of petals. She was overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of simple earthy beauty crammed into this one tiny patch of land.

She swiped at the wetness on her cheeks. Her grandmother would have loved every molecule of this place. It was on her knees, in the dirt, where she had taught Priya everything she knew about plants and gardening: the flowers that best attract pollinators, the way to rejuvenate tired soil, the complicated interchange of sunlight and sugar and water that transforms a tiny seed into a living plant. How to simply sit and enjoy the beautiful bounty.

Memories flooded back to her. Back on Earth, on her eighth birthday, she received her first pair of gardening gloves. The Council hadn’t yet begun to monopolize fabric production, and there was still an unlimited variety of colors and prints to choose from. Her gloves were cream-colored and padded with leather on the palms, with a tiny bluebird embroidered onto each cuff. She wore them out before she could even outgrow them.

Priya looked at her hands; took in the brown knuckles gnarled from age. As a young girl, she had plump, dimpled hands—an early source of insecurity. But her grandmother had always loved her hands. She would sandwich one of Priya’s between her own sturdy palms and press it to her heart. Priya’s own grandchildren had slender fingers, a trait they must have inherited from another branch of the family tree. It was almost unbelievable, she thought, that she was now as old as her own grandmother had been. Every day, she was reminded anew that she didn’t have much time left.

In the years leading up to the Takeover, there had been a concentrated effort to mitigate the lasting damage done to the environment during the Long War of the 21st century. For years, classrooms were plastered with brightly colored maps of the Former Nations that delineated the zones most damaged by nuclear warfare. Her grandmother’s generation was first made to feel the deep ecological angst and guilt at the damage that their ancestors had done; later, they were mobilized to restore the damaged environment. Thus followed a wave of youth-led initiatives that promised to make real change. It seemed that they really would be the ones to fix it all.

Her grandmother, smitten with the Council’s promises, was a lifelong plant enthusiast. Though the Environmental Deterioration Prevention Program had long since been officially dissolved by the time Priya was old enough to be in school, her grandmother made sure that she understood how to interact with the earth. Priya could still feel her leathery brown hands guiding Priya’s own small ones as she pointed to the flowers in her massive backyard garden: Achillea millefolium, Lupinus bicolor, Wisteria frutescens. Yarrow, miniature lupine, American wisteria. After a while, Priya remembered, the names blended together and all she saw was the tumbling riot of color that spanned trellis and flower bed and subsumed the entirety of what had once been a tidy lawn.

It was surprising, the way a few seemingly insignificant memories had wormed their way so deeply into her psyche that sixty years could vanish in an instant. Time was a rubber band, stretched taut one moment and flexible the next.

Now, here she was, in the place she had chosen. The engineers didn’t get to see what each Program participant decided to do with their time, or where they decided to spend their final moments. It was left up to each individual; the nature of the neural link was such that the Program could project even the most fantastical of places.

Priya sighed. She had known for a long time that she would end up in this wild and earthily beautiful place. The decision had been as easy as breathing.

It later came to light, years after her grandmother’s passing, that the EDPP had simply been a strategic part of the Council’s plan to unite the world’s youth against a common enemy—one that wasn’t the Council itself. Those in the inner sanctum had assumed, rightly, that any attempt to monopolize the world’s power would be extremely difficult to achieve. While it was true that the Long War had resulted in an initial streamlining, so to speak, of the world’s governments, the Council needed something that would generate real enthusiasm for the Takeover. The EDPP had fostered a generation of outspoken young people passionate about environmental restoration, but it had also done much more than that: years of pro-Council curriculum had primed her grandmother and her peers to welcome the Takeover with open arms.

For Priya’s grandmother, the Council was synonymous with environmental restoration and the return to nature that she had dreamed about since childhood. But she hadn’t lived to see the Council turn their backs on the very set of ideals that had allowed them to ingratiate themselves with the world’s youth and begin the Takeover process. As the Council swiftly incorporated themselves into almost every facet of daily life, environmental restoration fell out of fashion. During her lifetime, Priya had witnessed the Fifth Industrialization Wave and the expansion of space colonization. The Council insisted that Earth’s environmental problems didn’t have the same urgency they once had—after all, it was now just one of several habitable planets.

As the natural world began to decline once again, Priya tended her grandmother’s garden with a new fierceness. It was, to her, a sacred remnant of the greener world of her childhood. There, she could still feel her grandmother’s warm hands on her cheeks; smell the mingled scent of sunkissed greenery and mulch. But when the Council issued a draft to join Lunar Colony 4 and her name was called, she went. She didn’t have a choice. She pressed one of each kind of flower into the pages of a small book, hoping to keep with her the barest memento of her Earthly life. It was considered an unnecessary item and confiscated before Priya even stepped onto the transport shuttle.

At first, Priya wilted in her new environment like a sun-loving plant left in the shade. She thought she would die out there in space, just out of reach of Earth. But like the hardy wildflowers that adapt to harsh hillsides, she eventually tried to make the most of her life away from the world that she loved so much. She threw herself into her work as a colony member. She met a man who saw beauty in the Moon’s stark vastness, and in Priya’s warmth. Her children grew up in Earth’s shadow, listening eagerly to her stories and falling asleep to the whispered names of plants that they had never seen.

It had been fifty-eight years since she had rubbed soil between her fingertips.

She exhaled. Meandered along a pebbled path that gently wound through a young eucalyptus grove. Let the hem of the yellow dress drift in the dirt and the clear water of the creek. Sat down in the waving grass and let the sunshine permeate her cells. Smiled into the glare, at peace in the garden.

The Program was well-known to those living in the lunar colonies. Touted as an almost magical end-of-life experience, the Council had created it to sweeten the deal for those forced to leave their home planet. The chance to see what they wanted to see the most. Even though she was well aware that the bliss she was experiencing was nothing more than an expertly designed virtual dreamscape, Priya found it hard to reconcile with what her senses told her was real.

A small bird, a species she couldn’t remember the name of, landed on a branch near Priya’s sunny glade. It ruffled its feathers and cocked its head, observing her. She smiled. The bird opened its mouth mechanically and released a garbled, unnatural stream of sound. Priya shuddered, unsettled. Her throat was dry, and the rich soil she had been so overjoyed to sink her fingers into felt instead like parched and lifeless lunar dust.

She couldn’t stomach listening to the bird any longer. Unburdened by her cane or the pain in her back, she quickly traveled further down the path into a part of the garden she hadn’t yet explored. There, in the gentle sunlight, a familiar figure in a floppy hat bent over a brimming flower bed.

Her grandmother raised her head and beamed at her with that wonderful gap-toothed grin, and the tears streamed down Priya’s cheeks. She ran headlong into her grandmother’s coconut oil-scented embrace. She herself was now a hunched old woman, and none of it was real. But she was three again, repeating the peaceful names of flowers in her toddler’s lisp. She was eight again, proudly cradling a new seedling in her gloved hands. She was ten again, expertly trimming back the trellis-climbers alongside her grandmother. She was fourteen, laying in the rose-scented sun as her grandmother massaged oil into her long hair. She was seventeen, setting the outdoor table for tea with the forget-me-not china. She breathed in and out and let herself be held for a long time. Her grandmother stroked Priya’s white hair and took her old hand between both of her own. They looked like sisters. Priya cried for the Earth that she would never return to.

They had a conversation, there in that sublime ephemeral sunlight. Priya lived a life that her grandmother had only imagined would be possible one day. She spoke of her clever daughters, her kind son, her grandchildren, her life on the Moon. She spoke of the colony, of the advances they had made; of the beautiful unfiltered stars. But she could not tell her that the once-dreams of fixing what was broken had never, and would never, come to fruition. She must let her stay hopeful. To shatter the illusion of the Council’s environmental benevolence would be too cruel, surrounded as they were by bee-song and fox-glove.

So Priya knelt beside her grandmother, and they gardened. In that perfect halfway space between life and death, they got their hands dirty.

The first thing she notices when she wakes up, groggy, is the deep ache in her hip. The second thing she notices is the group of people standing around her bed. It takes her a moment to focus on them. They are her children, her grandchildren. She is close to her mandated death time, but she is not afraid. Once the lunar residents reach a certain age, they receive regular briefings on the process and soon, death merely becomes another part of the routine. Priya is grateful that her family will not mourn her loss. They have had plenty of time to prepare.

Her youngest grandchild, a three-year-old boy, touches her hand. He wants to know what she saw in the Program. What she wanted to see the most. She sandwiches his small hand in between her two sturdy palms and presses it to her heart. I was in a garden, she tells him. The most beautiful garden I have ever seen.

His round face creases in confusion. He is learning new words every day, at his age. He mouths garden a few times, though he will never taste its honeyed sunshine or plunge his tiny hand into its loamy soil. He withdraws his hand, unsure.

What’s that? He asks.